What is the difference between Stephen Curry and a 12 year old dribbling a basketball up the court? A 12 year is focusing on the ball whereas Stephen Curry is head up, analyzing teammates and opponents while dribbling changing speeds and directions. Curry’s graceful court skills may seem astonishing to most but are second nature to him. The ability to shoot and dribble without conscious awareness frees up focus for coordinating plays, checking the shot clock, and anticipating his opponents next moves.

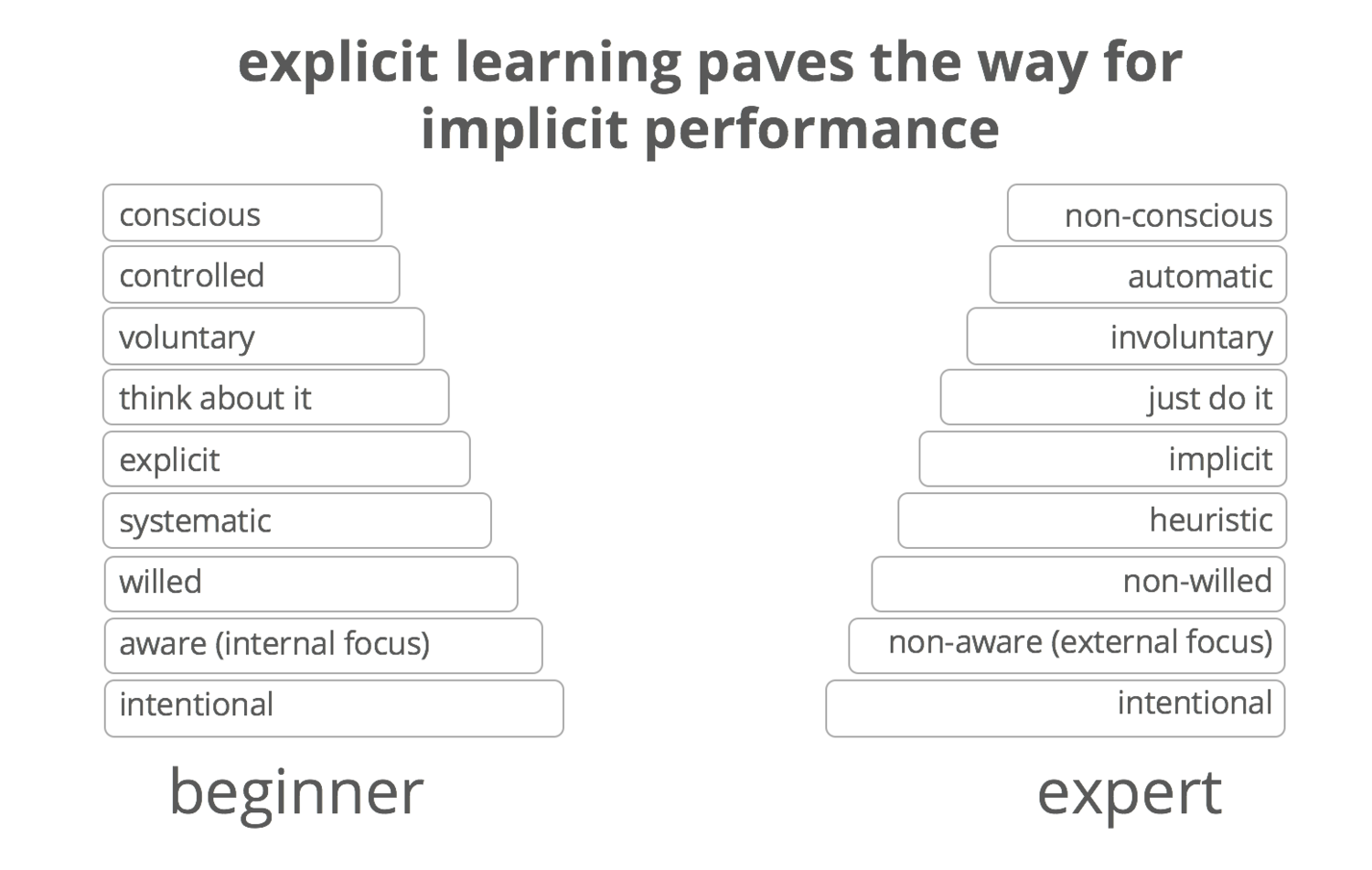

Sport psychologists have long studied skill acquisition and developing expertise which involves transitioning from conscious to non-consciously performing behaviors. The sport psychology research has considerable implications for cultivating an “implicit consumer expertise” where brands can shape subconscious purchasing patterns.

Unconscious Behavior is a Learnable Skill

Whether we shoot a basketball, drive a car, or are choose a yogurt at the grocery store – the behavior becomes unconscious when it is learned over time and with repetition. To master movements and acquire automaticity, people need to practice that particular skill so many times that it’s retained in your mind and muscles to retrieve the memory and complete the movement subconsciously.

REPETITION IS NECESSARY BUT NOT SUFFICIENT FOR SUBCONSCIOUS BEHAVIOR

No matter how much effort, practice, and persistence people put in they may never become a Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, or Usain Bolt. Why? Because they have not learned to automate their expertise and create implicit level of performance needed to excel in their sport (Hüttermann & Memmert, 2015).1 Stated differently, they have not gained the expertise and skills to make dribbling, shooting, swinging, running or throwing automatic, subconscious, less effortful and not requiring focused attention. Practice (reptetition) is necessary but not sufficient for creating implicit expertise in performing behaviors.

Unconscious is Always Susceptible to Consciousness

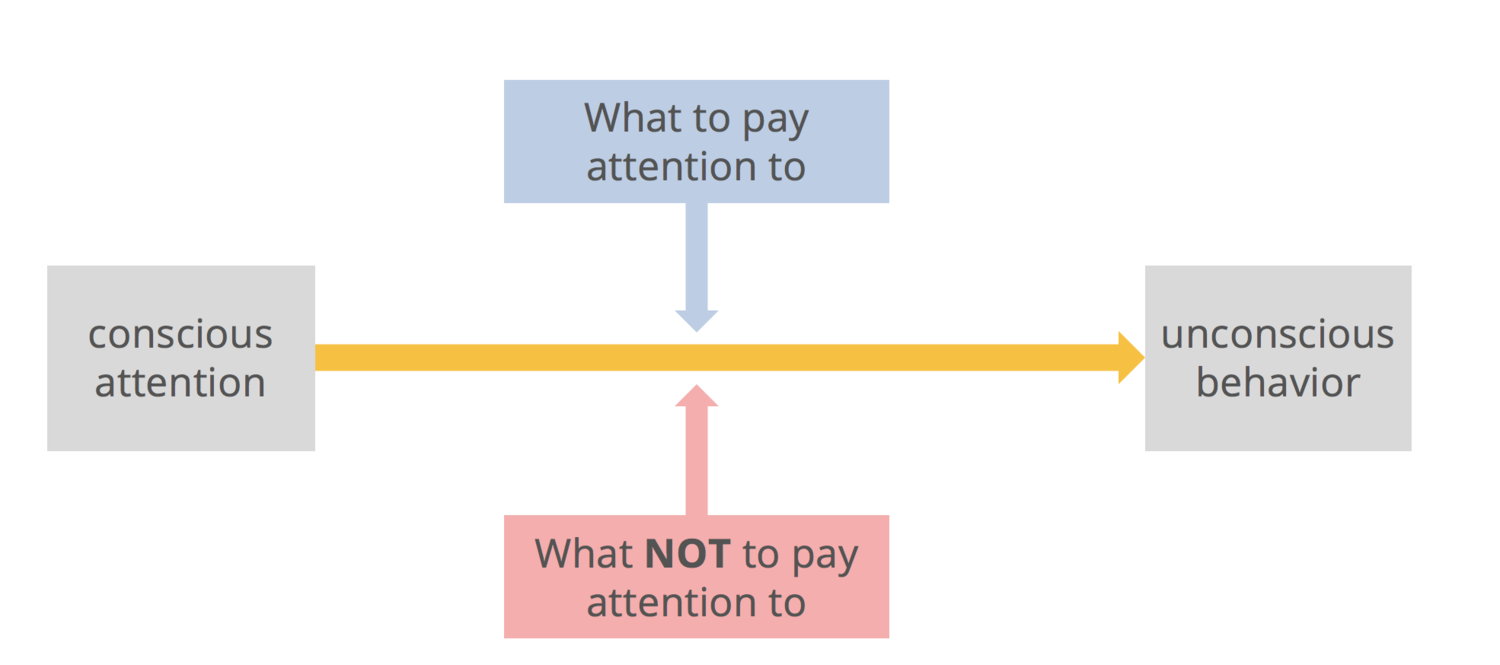

Even the most routine behaviors (e.g., brushing our teeth, eating breakfast) that can be performed unconsciously and automatically every morning are not always protected from consciousness. Our everyday decisions can easily be swayed or nudged to deviate from the habitual. Control over cognitive and attentional processes will always be a factor. For example, many athletes are familiar with ‘choking’, overthinking, distraction, perceptions of inadequacy, overly elevated emotions such as anxiety or fear of failure which all may lead to disrupting the automatic performance of the behavior (Baumeister, 1984).2 Unconscious behavioral execution requires developing a process requiring a combination of thoughtful attention and strategic inattention to control the interplay of factors and forces that govern our behavior.

Where We Focus & Attention is Key!!

The wrong focus can hinder performance (Wulf & Prinz, 2001).3 Many have shot a basketball, hit a golf ball or ran a race and may have experienced how the wrong focus can mess up our shot or ability to run. For example, when I run and if I start thinking about my strides, muscle fatigue or breathing my performance declines (known as an internal focus). Rather, I aim for an external focus by consciously focusing on crossing the finishing line as opposed to my running technique. Michael Jordan and Tiger woods have developed this external focus to avoid thinking about their technique and the crowd. Taking an external focus allows the automatic execution and prevents choking (Singer, 2001).4

3 Strategies to Create Implicit Consumer Expertise

At a high level the goal should be to take a customer from explicit to implicit level of performance in purchasing your product. Conscious learning prevails at first, with nonconscious performance demonstrated at the highest level of proficiency. To do this one must be in an optimal, self-regulated state in order to develop an customer strategy that becomes effortless and automatic.

- Develop a Customer Pre-Performance Routine. Pre-performance routines are key to expertise. Can you imagine Jordan or Tiger Woods performance without their warm ups? It integrates goal intention with visual and proprioceptive mechanisms, which in turn enhances decision-making, response selection and action processes. Creating a customer pre-performance routine by priming an external focus can facilitate the unconscious behavior.

- Create Customer ‘Flow’ States. Help customers develop cognitive strategies to master the act. To master movements requires great precision in movement execution demonstrated repeatedly over many occasions, against a variety of opponents and in various environments (Derry et al., 1986).5 Help create customer flow and resilience by providing tools to master the shopping (overwhelming choice, distractions, stress). Also, keep them consistent!

- Prevent Distractions & Choking. Under intense and personally meaningful competition, there is a tendency for anxiety/arousal to be heightened to such a degree that controlled (conscious and deliberate) processing sometimes takes over from automatic processing. Help customers by removing things that disrupt their flow (and create a conscious distraction) – make choice easy, remove high arousal content, and prevent competition from disrupting the shopping journey.

Citations

- Hüttermann, S., & Memmert, D. (2015). The influence of motivational and mood states on visual attention: A quantification of systematic differences and casual changes in subjects’ focus of attention. Cognition and emotion.

- Baumeister, R. F. (1984). Choking under pressure: self-consciousness and paradoxical effects of incentives on skillful performance. Journal of personality and social psychology.

- Wulf, G., & Prinz, W. (2001). Directing attention to movement effects enhances learning: A review. Psychonomic bulletin & review

- Singer, R. N. (2001). Preperformance state, routines, and automaticity: What does it take to realize expertise in self-paced events?. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology.

- Derry, S. J., & Murphy, D. A. (1986). Designing systems that train learning ability: From theory to practice. Review of educational research.