How losing my brother helped me find the strength to change

December 4, 2002

My older brother Matt’s forehead was on fire with a fever. He complained of throbbing pains; purple dots like pen marks were scattered across his pale skin. We didn’t know what was wrong. I helped peel Matt’s limp 5’10 frame off the bed, quickly put a coat on him, and carried him into the family van.

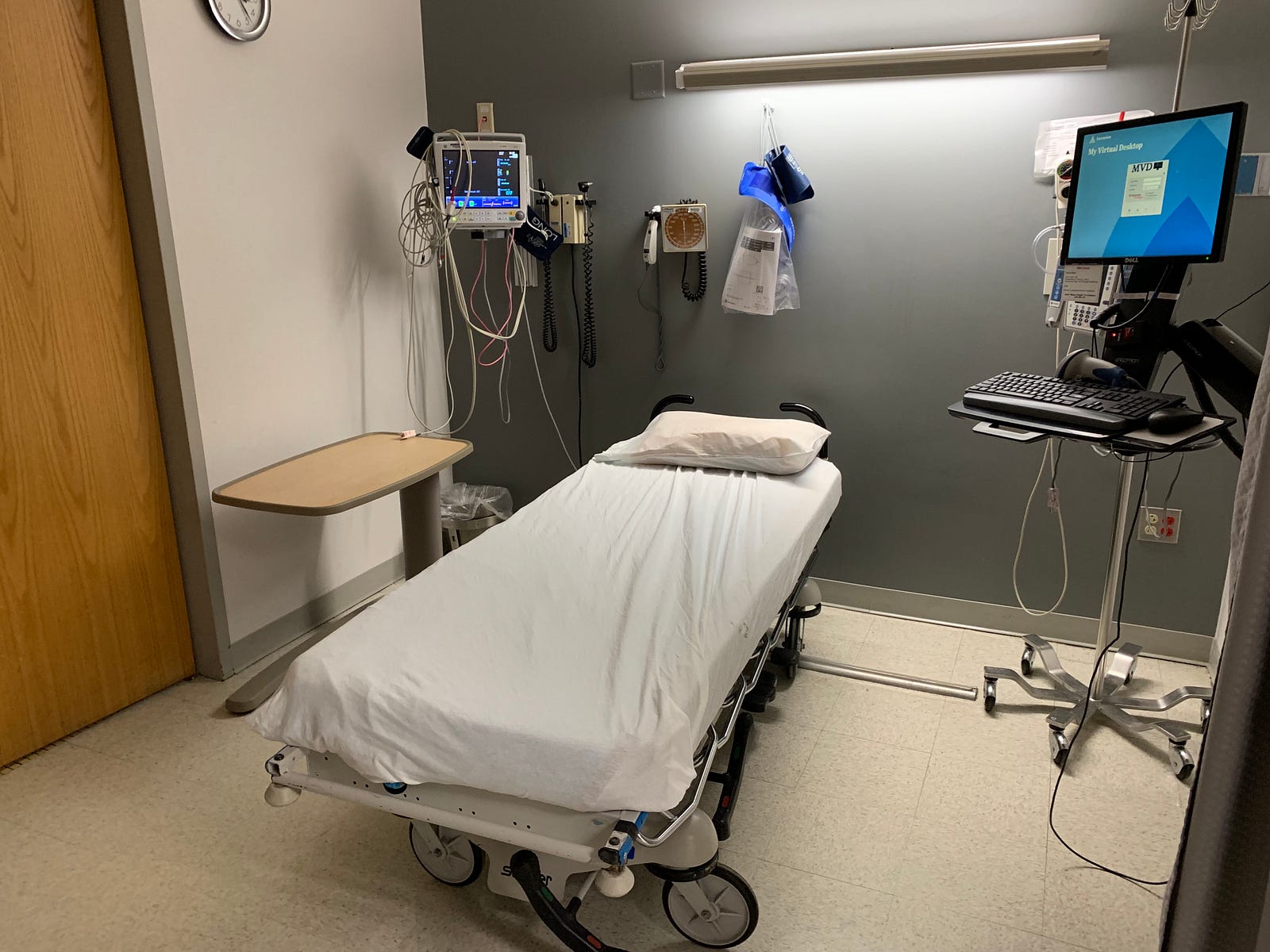

We arrived at the emergency room at 10 p.m., into the odors of sterile air and plastic waiting room chairs. After Matt and Mom disappeared, I was left alone in the waiting area, hungry and hoping they would hurry up and prescribe my brother medicine so we could get back home. My hunger became a crippling uncertainty, an appetite for answers.

An hour went by. My Dad arrived from work. We followed a nurse, slowing as Matt’s curses pierced the quiet hospital hallway. We stepped inside a shoe-box-sized room. Matt lay limp and constrained on a thin mattress; steel metal railings kept him in place. He was plugged into more tubes and wires than the cords to and from my Xbox.

Throughout the night, doctors and nurses stormed in and out of Matt’s room. It seemed like they used every machine they had on Matt, every scan, test, pump, tube, and needle. Nobody could figure out what was wrong.

The rhythmic pattern of Matt’s vitals went from Beethoven to Metallica. I will never forget Matt’s heartbeat, the sound of his life taking a nose dive as the digits on the machine dropped.

Matt’s internal organs were failing. His heart no longer pumped enough blood. I don’t remember how long it went on, but it seemed forever.

The last memory I have of Matt was my trembling tree stump legs, holding up my overweight teenage body as I stood at the foot of his hospital bed. His big black and red Air Jordans faced me. My father took over CPR to keep Matt alive. In later years, Mom claimed this never happened. Dad doesn’t recall, but my image of it is clear.

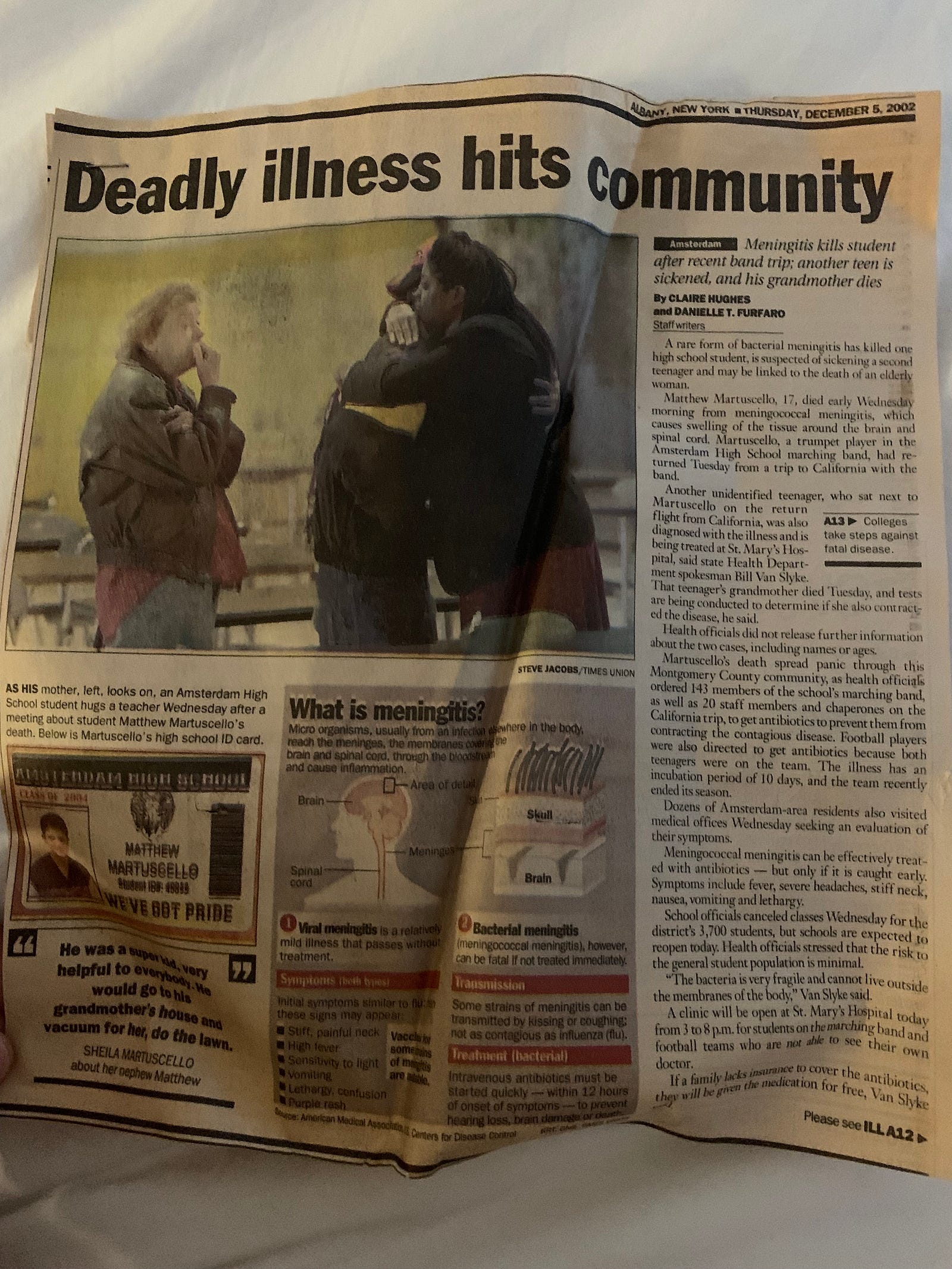

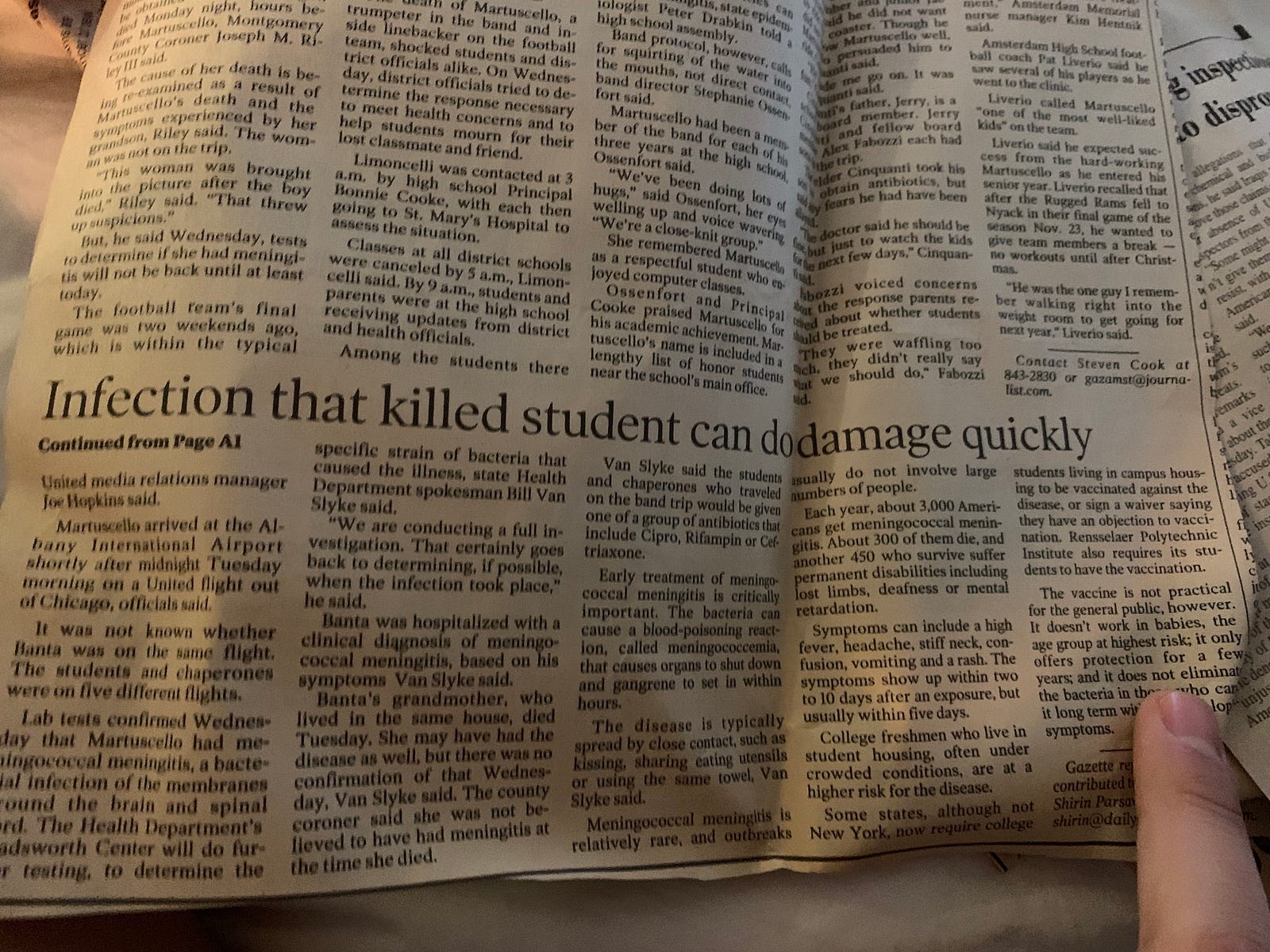

The cause of death was bacterial meningitis, a rare viral disease. The loss of Matt sparked a city-wide scare, prompting New York state officials to close the Amsterdam school district. If Matt could die 36 hours after sipping from someone’s water bottle, might not the hundreds of other people around him die, too?

Over the next few days, my family received never-ending deliveries, catered meals, cakes, cookies, flowers, and cards. I was numb to everything, except the food. Growing up in a tight-knit Italian household, we were raised on two pillars: family and food. Even in our grief, skipping a family pasta meal was worse than committing fraud, and seconds were mandatory. After a heaping plate of al dente pasta and meatballs made with hand-picked ingredients from the garden, Grandma would ask, “Have you had enough?” She’d shovel more onto my plate before I could answer.

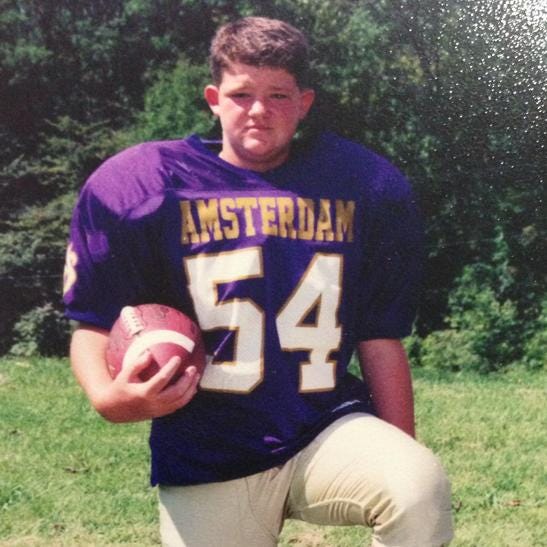

Growing up, I was the fat kid. I rationalized my 40-inch waistline with football. The formula was simple: eat more, get bigger, and be better at football. I was a force, a leading tackler, and a defensive lineman on the JV team. I was good, but Matt had always inspired me. He played varsity ball, practiced directly across the field from me, and baked the value of hard work into his purple and gold #54 jersey. Later, when we won the New York State high school football championship, I wore Matt’s number.

I spent the days following my brother’s funeral splitting my time between crushing levels of halo in my room and consuming heaping portions of lasagna in the kitchen, washing them down with cake and lemon cookies. It was my way of coping. I didn’t care to talk to anyone, vent, or even cry. Coping seemed to come easy for Dad. He deepened his anchor and clung to his faith. Mom confronted her long-held beliefs. “No…Noo…Noooo,” she moaned as if this were all a dream. Mom avoided conversations that would remind her of Matt. She had no idea why she had to bury her son, so she tucked him into a place where she could go on living. At the time, I couldn’t blame her. Today? Maybe I do.

Savoring the Truth about Death…

Another way I managed was through curiosity about death. It became an obsession. I might walk out of a coffee shop and get slammed by a bus. Or choke on nuts or could get gunned down just by being in the wrong place at the wrong time. The possibilities were endless. I savored this truth. My twice-daily burger binges continued to contribute to my waist and my breasts grew bigger than my sister’s. Ronald McDonald shares the blame with my grandmother’s pasta for helping me become another statistic in the obesity epidemic.

Matt’s death made my future of continuing to overeat and justifying my choices a very real problem. I began to visualize a 50 year-old virgin not fitting through doors, unable to date or fit into society. Matt’s absence made my own endgame top-of-mind. I started to think about what people would say at my funeral. What impact did Jason have on others, on the world? What legacy did Jason leave behind? Until now my influence extended only as far as the width of my plate and finishing others’ plates. I’d had enough. No more Marshmallow. No more sucker punches or excuses. Time for a change.

Before Matt died, our lives were deeply connected. We shared a room, beds two feet apart. We shared the same closet, wore each other’s clothes except the Cowboys jersey (his) and the Giants jersey (mine). We had the same friends, rode the same bus, played sports (basketball, football, and baseball), and wore the same numbers when we weren’t on the same teams.

Inevitably, Matt’s death gave me the power to take control of my life and my weight. His passing forced me to take responsibility for my life, and stop being part of the crowd who wanted change but did nothing to get it. If I wanted to change, I had to initiate it. Over the following 18 months, I became ruthless about my choices. I showed up at the gym, rain, snow, or shine. No personal trainer, parents, or doctors to push me, only the commitment I made to myself and Matt. In the case of food, instead of action, I developed the ability to stop, to put the fork down, which affected my weight the most. Matt stood by me every step of the way.

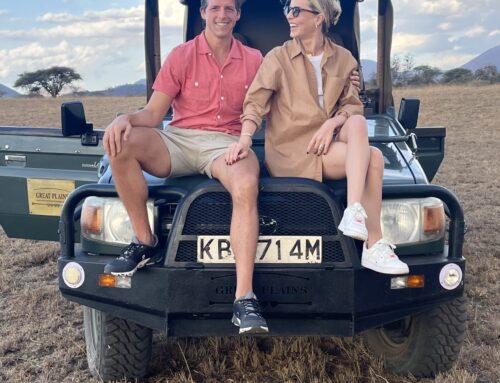

Losing my brother was tragic. While painful, I worked hard to turn it into a positive, powerful event in my life. Matt’s death helped me see my future and the choices needed to create lasting change. Once I gained control of myself, worry and fear became unnecessary parts of my life, leaving me a clear focus on the things and people most valuable. I lost over one hundred pounds, earned 3 degrees, ran 5 marathons, and traveled to twenty countries. Now I’m writing my story. And Matt’s, because mine would have never started if his hadn’t ended.

Reflecting on 20 Years Since Matt’s Death

The past 20 years have been without Matt but I feel he has never left my side. Every waking morning, I see Matt’s framed jersey on the wall beside my bed. The jersey marred with sweat, dirt and turf stains, signed by his teammates, serves like a hit of adrenaline to accelerate my days. It also is a reminder that my end will come, which serves as a source of energy, resolve, and enthusiasm to achieve what I want out of life.

I moved to NYC in 2018 to further my career and find my future wife. After one year in NYC, I met a stunningly beautiful blond woman who asked to go on a date. We met at a small restaurant on Stone Street in lower manhattan where I saw the roman numeral thirteen tattooed on her wrist. Curiously I asked, “what does the thirteen mean?” She replied, “it is my birthday. October 13th.” I gasped. October 13 was the same birthday as my brother Matt. Today we are happily married and are welcoming our first child in January 2023…

Theodore “Matthew” Martuscello.