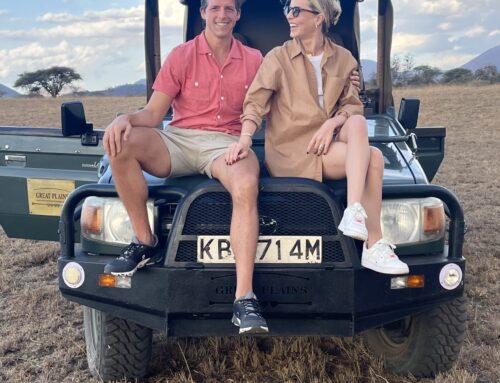

Imagine eating ice-cream everyday and being healthy? That day is finally here. There used to be just ice-cream, cookies, chips, and candy but now there is healthy ice cream, protein cookies, kale chips, and candy bars disguised as granola bars. Brands have found a soft spot in human thinking and have blurred the lines between eating good and bad.

A “HEALTH” Trend Gone Wrong.

Customers want to be healthier. Brands recognized this and are actively trying to profit from this emerging trend. Whether it is simply sprinkling some marketing buzz words (natural, fresh, clean, protein) or making actual product changes (reduced calories, gluten free, low fat, no sugar) — brands are trying to help people eat healthier. It is amazing in today’s modern eating environment we can eat our favorite chips, cookies, cakes, and candy bars — and be healthy. Or at least think we are…

The Problem Everyone Overlooks: Food Learning.

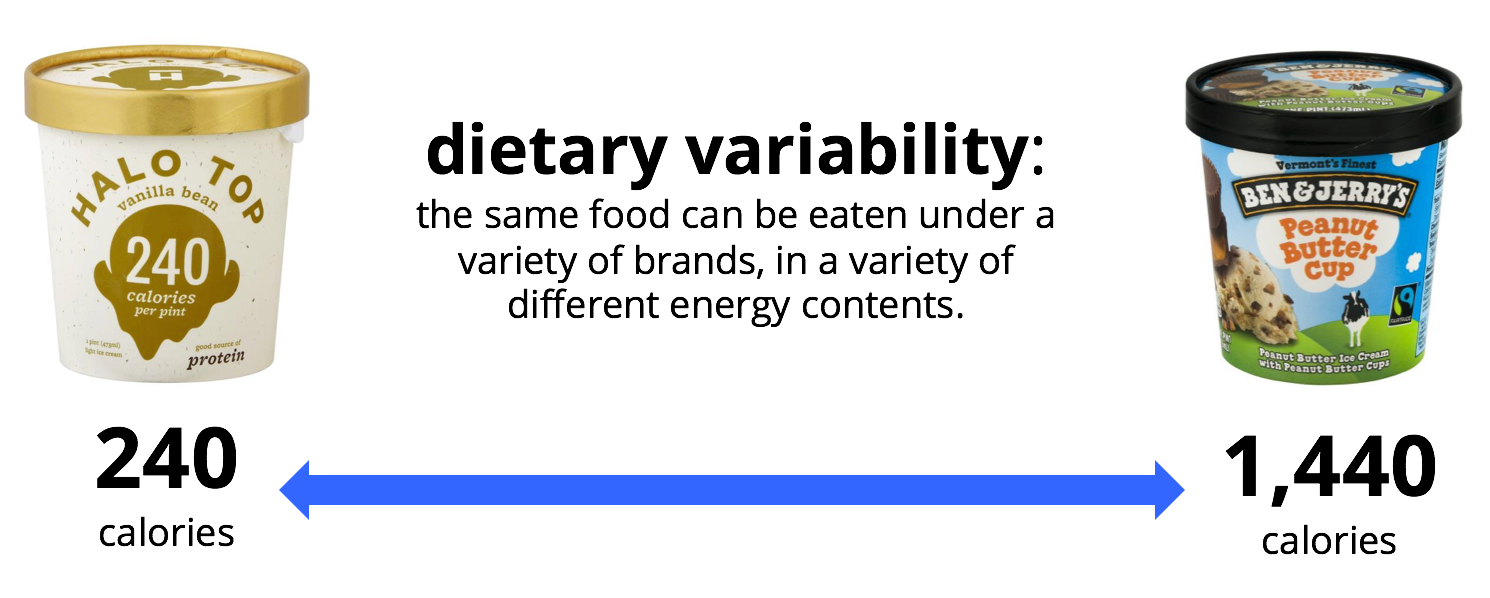

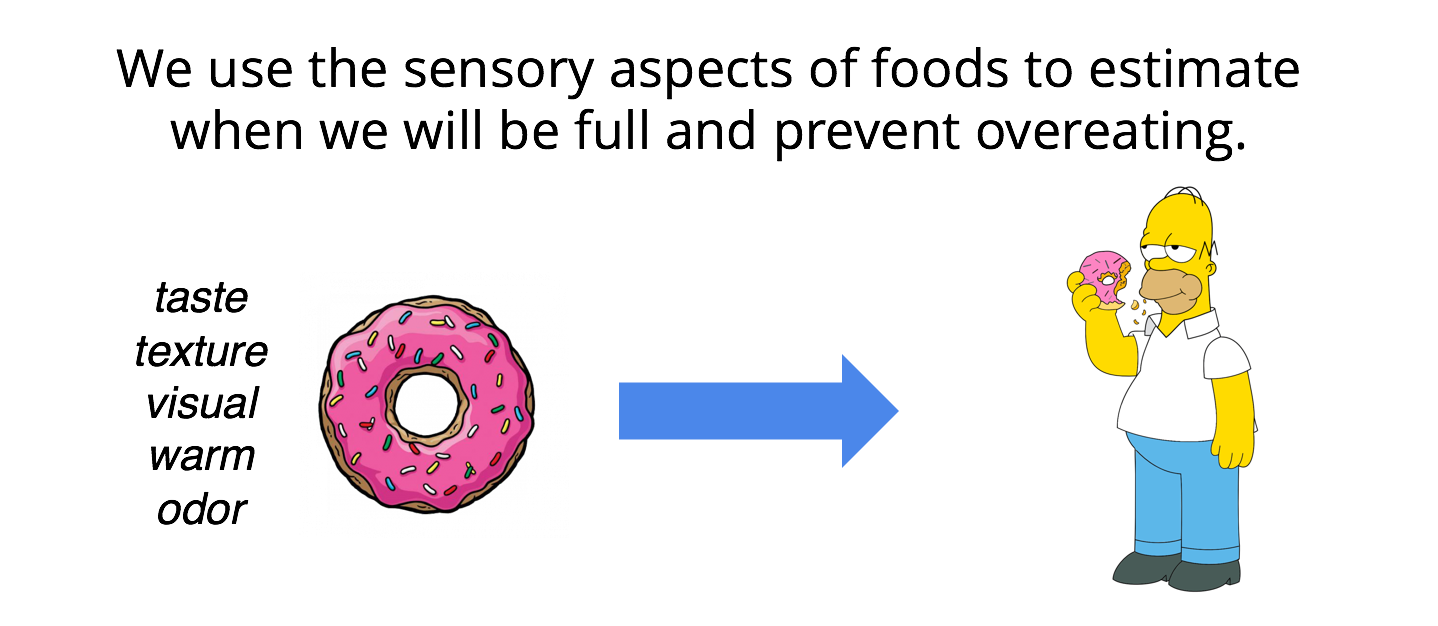

When we eat we learn two things: 1) what we like to eat (hedonic learning) and 2) how to regulate how much food to eat (satiety learning). For example, when Homer Simpson first ate donuts he quickly learned he liked donuts (hedonic) and through repeated consumption he also learns how much to eat to ‘feel full’ (satiety). Why is satiety learning important? If Homer eats 6 donuts and feels stuffed he knows to eat less than 6 donuts next time. Although counting donuts or calories can be used as a gauge to prevent overeating, most people don’t count. This is where satiety learning comes into play.

Non-conscious Satiety Learning

In addition to using sensory cues (taste, texture, color) to guide our taste preferences, we also use sensory aspects to predict our satiety level. For example, through repeatedly eating the same donuts, Homer subconsciously associates the taste, texture, and smell (sensory cues) which map to his ‘feeling of fullness’ and allows him to automatically cut off consumption. You may be able to relate to using sensory cues to estimate energy densities of foods for instance: “liquids” are associated with less calories, “thick” or “heavy” foods as unhealthy, “creamy” with fattening, or “light” with healthy.

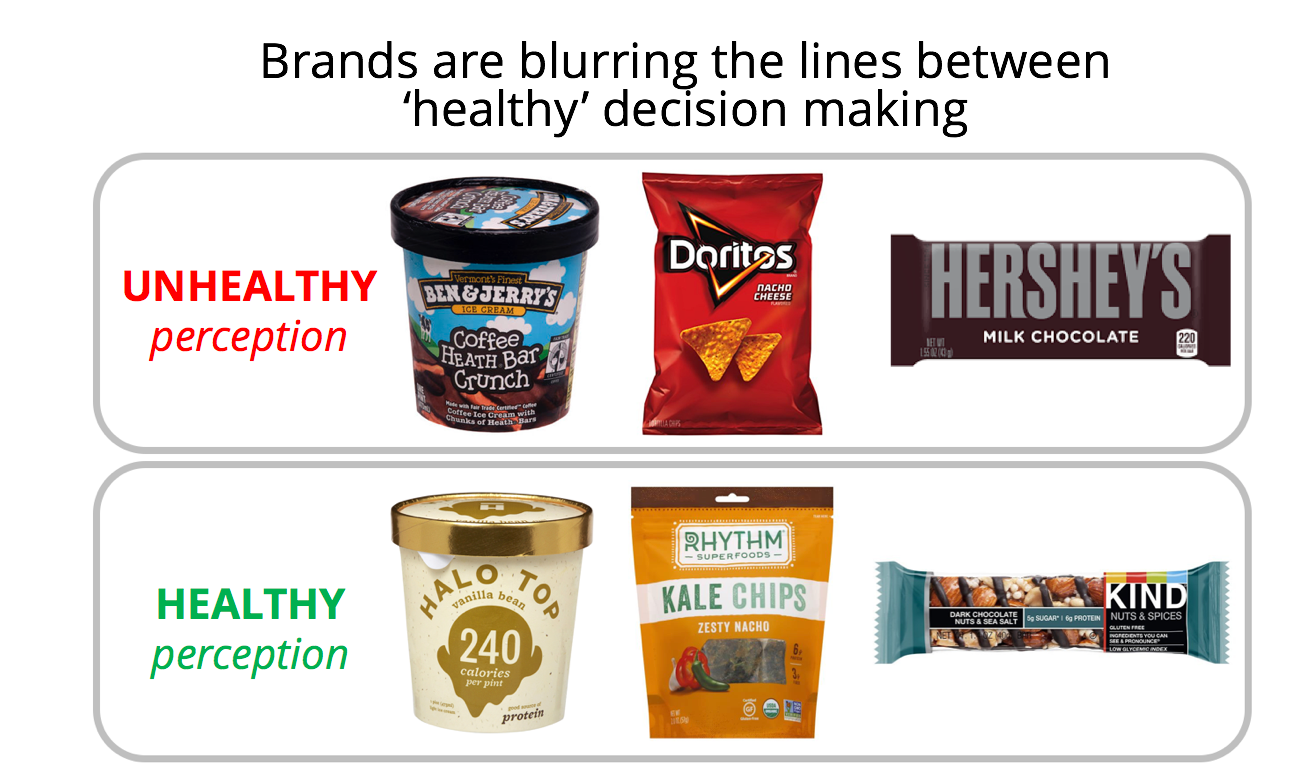

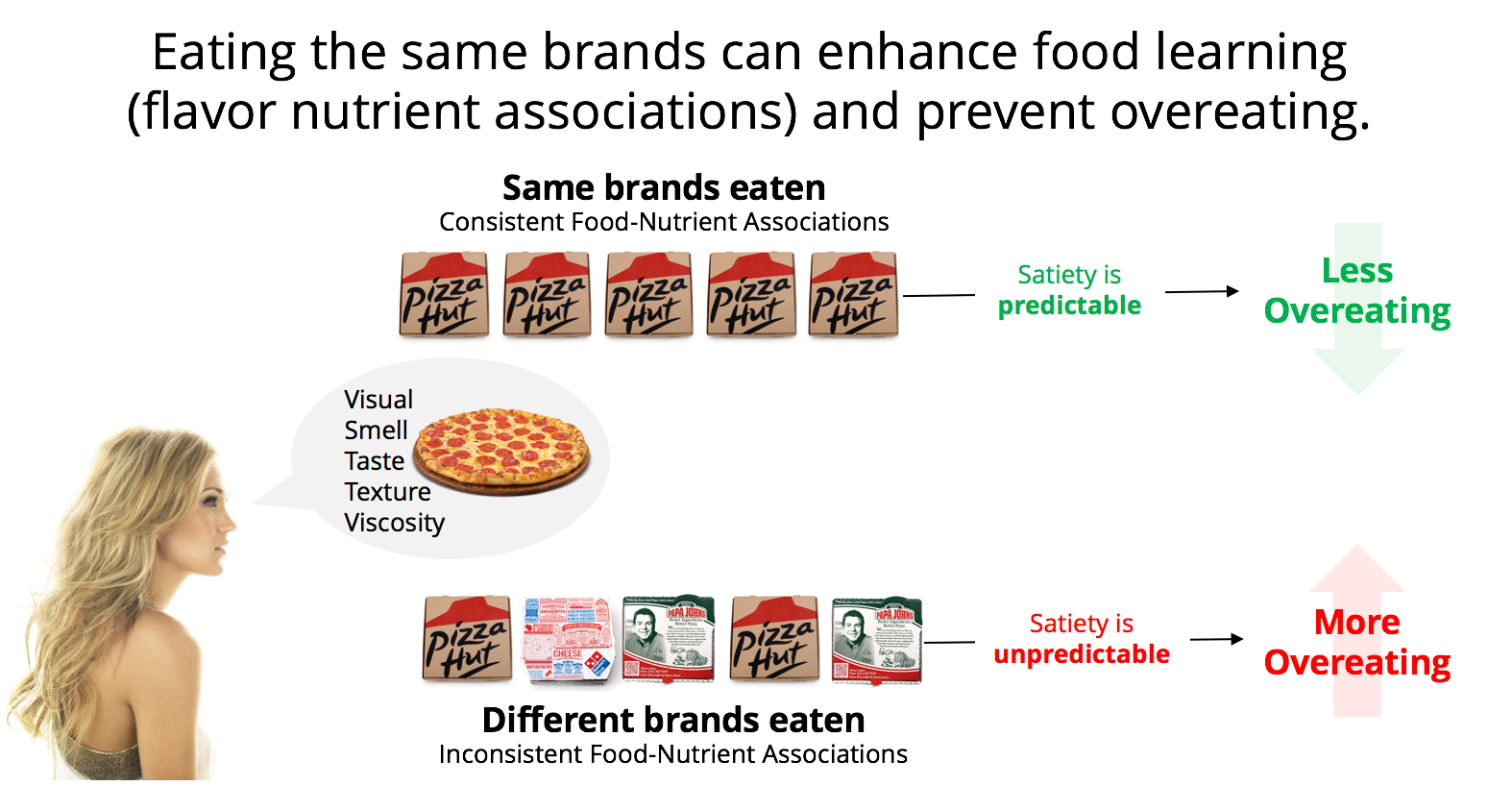

Learning flavor-nutrient associations (light, thick, heavy, creamy, soft, textures, etc.) is critical to subconsciously managing our food intake. With brands creating ‘healthy’ variants of ‘unhealthy foods’ this creates inconsistencies for our brains food reward learning. Dietary variability prevents formation of a reliable flavor-nutrient associations and disrupt the cognitive control of food intake (Martin, 2016). Put more concretely, by consuming pints of ice cream that are 240 calories and other similar sized portions that are 1440 calories it throws off our brains ability to subconsciously match sensory cues to energy densities.

Another common example, is consuming no calorie Sweet-n-Lo. Consuming artificial sweeteners disrupt our brains learning by creating new associations of ‘sweet taste’ with no calories. Over time, these associations may carryover to eating other sugary and sweet foods that we will associate no calories and as a result over consume. In short, the new breed of ‘healthy’ food products (e.g., low sugar, fat-free, no calorie) disrupt our pairing with actual energy which lead to overeating.

What to do about it?

- Eat a variety, but less variability. Eating wide variety of food groups helps to ensure we get sufficient micronutrients (vitamins, minerals, and fiber, etc.). Within food groups, it is important for the brain to develop consistent food associations which help regulate our intake (see image below).

- Avoid modified or processed foods. Ice cream and peanut butter should have fat it in, and honey and soda should have sugar in it. Cutting a few extra calories on the front end, may hurt you in the long run by disrupting ‘satiety learning’.

- Brands can market food products aligned with taste expectations. This is a huge opportunity for legacy brands who want to win the war on healthy. Developing marketing to change the conversation around what is means to be healthy. For example, a Hersey’s chocolate bar is nutritionally similar to Kind bars yet people think they eat ‘healthy’.

Citations:

- Hardman, C. A., Ferriday, D., Kyle, L., Rogers, P. J., & Brunstrom, J. M. (2015). So many brands and varieties to choose from: does this compromise the control of food intake in humans? PLoS One.

- Martin, A. A. (2016). Why can’t we control our food intake? The downside of dietary variety on learned satiety responses. Physiology & behavior.

- McCrickerd, K., & Forde, C. G. (2016). Sensory influences on food intake control: moving beyond palatability. Obesity Reviews.

- Rozin, P., & Zellner, D. (1985). The role of Pavlovian conditioning in the acquisition of food likes and dislikes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.