Every wants to develop habits but many struggle in doing so. The commonly prescribed ingredients (cue, routine, reward) for successful habit development are generally necessary but largely insufficient to create automaticity and sustain a behavior. If you have not already tried to build a habit – see for yourself. Trying to habituate even the simplest behavior (e.g., take a daily vitamin) into our daily grind is much harder then books sell us.

Why most habits fail…

How good would any sports team be if they spent their season only practicing offense and not defense? Most likely not very successful. This is the problem with current approaches to building habits. We largely focus on developing a habit (offense) while not considering the influences that disrupt a habit (defense).

Habit as an Impulse

Habits have been traditionally portrayed as a process, where over sufficient time and practice, a behavior will “lock” into a habit (reach a point of automaticity, not requiring attention or deliberate thinking). Thinking of habits in 2 stages where we cross a threshold moving from hard/effortful to easy/automatic is problematic.

Just as the most dominate sports teams are susceptible to losing so are the most engrained habits susceptible to failing us.

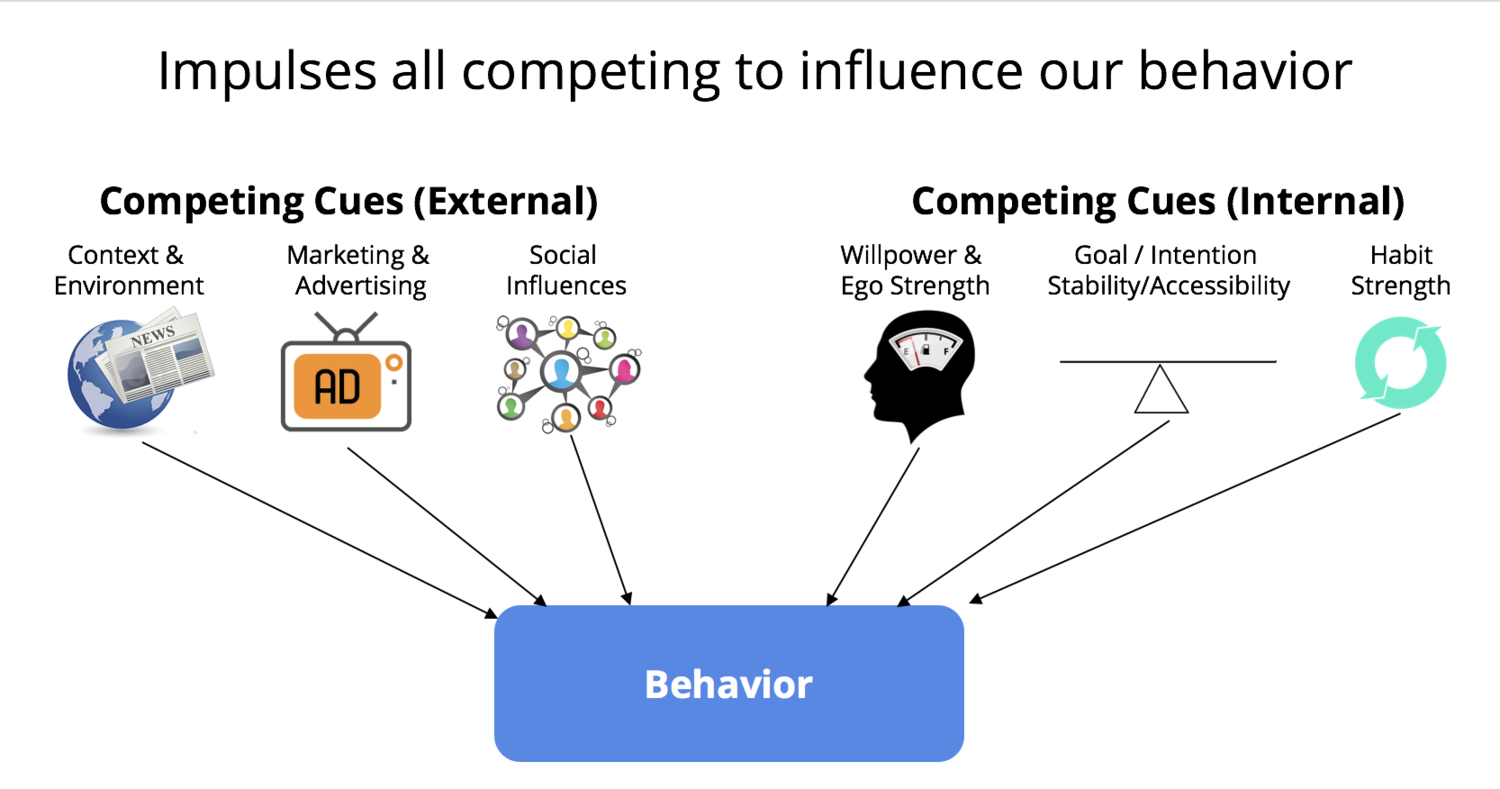

Instead of thinking of habits as this protected euphoria of behavioral automaticity, it is best to think of habits as impulses competing for control of our behavior (Gardner, 2015).1 At any given time, multiple impulses compete to control our actions, and the impulse that is strongest, or least strongly opposed, in that moment will determine the behavior (Michie & West, 2013).2 The more we practice a routine the stronger the “habit impulse” and increase the likelihood that behavior will be a product of our habit.

The strength of the impulse is key! For example, a fast food advertisement notification (ad impulse) gracefully sent to your phone right before lunch can derail a healthy eating habit (impulse). Or our kids morning shenanigans (social impulse) can quickly rearrange our habitualized morning routine (impulse).

When we understand habits are impulses competing for our behavior then there are two ways to strengthen habit impulses: 1) habit offense, and 2) habit defense.

Habit Offense – Builds Habits

When most people talk about habits they are referring to “habit offense”. It involves all that fun stuff of finding environmental cues, creating repetition and rewarding a routine. Through repeated practice of a routine (circle or habit loop), we develop a “habit impulse” (stimulus-response associations) that will trigger a behavior. The more we practice and reinforce the routine the stronger the habit impulse.

What you do to create a habit, is not what you do to keep a habit.

Habit Defense – Keeps Habits

At any given point in time, we are bombarded with sensory information competing for our attention and energy. Our behavior is a valuable commodity that is preyed upon by our text messages, TV ads, facebook notifications, #Trump tweets, co-workers complaints, news updates and amongst others. “Habit defense” is what protects behavioral routines from these competing impulses.

To summarize, habit offense develops a habit (think of it like scoring in sports), and habit defense prepares us not to fail (think of it like not letting the other team score).

2 Keys to Habit Defense

Defense, whether in sports or business, is about removing or minimizing the competition. Building habit defense comes down to two things: remove or minimize obstacles that drain our 1) energy and 2) attention.

- Energy. Any habits worth achieving generally requires more effort or energy then doing nothing (status quo bias; Kahneman et al., 1991).3 Our brain and bodies follow the path of least resistance (free energy principle; Friston et al., 2010)4 which always puts us in a battle against ourselves. Our internal energy saving devices always bias the appeal of: stairs over elevator, couch over gym, fast food over cooking and all other paths of least resistance. The goal is to align behavioral routines with our energy cycles (e.g., prioritizing harder behaviors earlier in the day).

- Attention. Distractions fundamentally rob the success of our “habit impulses” that we spent time, effort and energy building. Competing impulses simply shift our attentional focus by heightening the relative attractiveness which can change our behavior in the moment. The goal is to minimize or remove distractions and other impulsive cues in the environment that lead rob us from keeping habits. By removing temptations in our attention it is like playing hockey and the other team is playing with less players.

Citations

- Gardner, B. (2015). A review and analysis of the use of ‘habit’ in understanding, predicting and influencing health-related behaviour. Health Psychology Review.

- Michie, S., & West, R. (2013). Behaviour change theory and evidence: a presentation to Government. Health Psychology Review.

- Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. The Journal of Economic Perspectives.

- Friston, K. (2009). The free-energy principle: a rough guide to the brain?. Trends in cognitive sciences.